It was a little over a year ago that a mysterious illness emerged from Wuhan, China, and altered the trajectory of our global economy. By almost every conceivable measure, the COVID-19 pandemic delivered a swift and massive shock to our system — one whose ripple effects are likely to be permanent.

Both as a public health and economic crisis, COVID-19 is unprecedented in its global scale and reach. As the second wave of infections ramps up, we are now beginning to piece together a more complete picture of the state of the global economy during COVID.

It isn’t pretty.

Reassuringly, from the perspective of Canadians and the housing market, the outlook is much more nuanced.

Employment: High-Wage Earners Up, Low-Wage and Renters Down

Much has been said about the impact of government lockdowns on overall employment. More than 3 million Canadians lost their jobs in March and April as provinces ramped up efforts to contain the virus. The labour market has been adding jobs consistently over the past six months, but a closer look at the data shows a tale of two recoveries.

Low-wage earners and recent university graduates have been adversely affected by the lockdowns. Not only were young workers disproportionately impacted by the initial layoffs, but the industries in which they are most represented have been slower to recover.

On the other end of the spectrum, higher-wage earners who remained employed during the pandemic have seen their savings soar. This cohort is purchasing homes and investment properties at an accelerated pace, which has contributed to a record rise in home prices. Property investors, however, are dealing with a rise in vacancies as demand from young people and low-income workers continues to decline, especially in major urban centres like Toronto and Vancouver

Despite areas of weakness, higher-wage earners who bought homes during the pandemic likely made a wise investment decision. Capital Economics believes home prices will rise 12% by the end of 2022.

For the average homebuyer, rising prices are being offset by record low mortgage rates. Data from RateSpy.com show that the average five-year fixed rate fell to a new all-time low of 1.99% in September, down from 3.04% at the end of 2019 and 3.78% at the end of 2018. Capital Economics says these lower rates have raised the average home price that a median family can afford to finance by 13% from 2019 and 24% from 2018.

Income and Debt: Short-Term Gain, Long-Term Pain?

It’s conventional to think that economic recessions reduce income and lead to higher debt as the recently unemployed rely on credit to make ends meet. But COVID-19 hasn’t been an ordinary recession, not by a long shot.

Canada’s economic and fiscal response to the pandemic cost an estimated $382 billion, or roughly 19% of our gross domestic product. With much of that money being directly funneled to individuals and businesses, some incomes increased during the pandemic. Combined with a decline in discretionary spending due to lockdowns, the overall debt level of Canadians decreased in 2020. That’s a positive from the perspective of affordability and home buying, especially in an environment of record-low interest rates.

The long-term impact of massive deficit spending is yet to be seen, however. It’s very likely that the chickens will come home to roost in the coming years as the feds try to dig us out of a $328.5 billion deficit.

On a macro level, Canadians are expected to see an average annual salary increase of 1.6% in 2020, according to Morneau Shepell. That’s down sharply from the 2.4% increase of 2019. Base salaries are expected to increase by an average of 1.9% in 2021.

Adjusted Spending Patterns: Less Spending Means More Saving

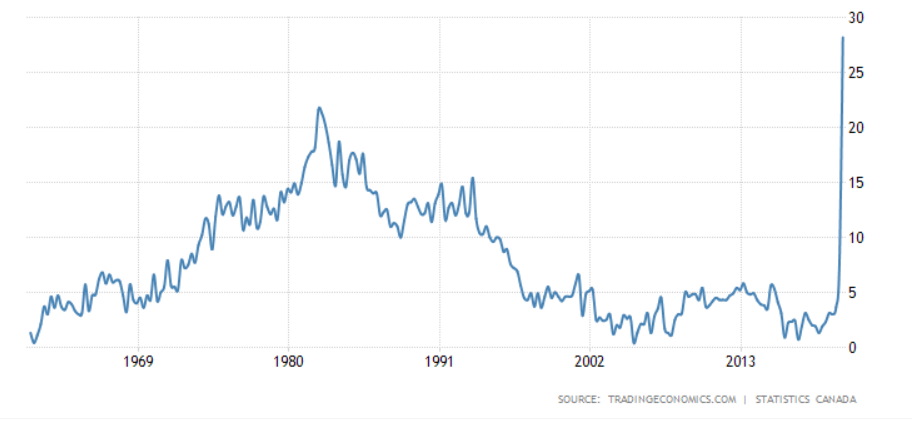

If there’s one positive to take from the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s that households dramatically increased their savings rate. Canadians saved 7.6% of their disposable income in the first quarter, the highest rate since 1996. This was followed by a second-quarter spike to 28.2%, the highest since at least 1961, according to Statistics Canada.

Average Household Savings Rate in Canada

Mainstream economists often speak of a trade-off that comes with a high savings rate. While individual households may benefit from high savings, on an economy-wide scale, money that could be spent on goods and services may remain idle. As much of Canada’s economy is consumer driven, such a lack of spending could adversely impact employment and inflation.

However, in this recession it didn’t take long for consumer spending to bounce back. According to RBC, spending was just above year-ago levels in early November, though lockdown-sensitive categories like restaurants and travel remained down. Early data show that spending on books, music and entertainment products are rising on a year-over-year basis. Live entertainment – such as concerts, art and movies, on the other hand remains negative.

While it’s clear that Canadians are spending again, their preferences have shifted due to the pandemic.

Population and Demographics: Cities Out, Suburbs In

Local and regional migration trends are perhaps the most convincing sign that COVID-19 has shifted consumer behaviour. Across Canada, appetite for single-family homes has surged amid the pandemic, whereas demand for downtown condominiums, as well as other housing in dense urban areas, has declined.

More people are opting for the suburbs because they no longer commute for work. As a result, new construction projects for single-family homes are surging whereas other types of dwellings, including apartments and condos, are in decline.

The condo market has lost another key demand driver in net migration. With the federal government shutting down the border amid the pandemic, net migration has declined a whopping 94%. According to RBC, immigration is unlikely to rebound to pre-pandemic levels anytime soon.

The collapse of interprovincial migration has also been a factor amid the pandemic, as provinces and regions advised against and put restrictions on travel. Atlantic Canada, for example, had allowed for free movement within the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island, whereas those entering the region from the rest of Canada were required to quarantine for 14 days. The so-called Atlantic Bubble ended on Nov. 23 with the withdrawal of Newfoundland and Labrador and P.E.I.

Rental Rates and Yields

With the flow of new permanent residents to Toronto and Vancouver essentially cut off, the condo market has taken a hit, both in terms of sales and rent. Condo listings in major cities have risen throughout the pandemic as vacancies continued to rise.

On a national level, average rent prices have declined substantially amid the pandemic.

Source: Rentals.ca

In major cities like Toronto, Mississauga, Ottawa and Winnipeg, average rent has declined by double-digit percentages compared with 2019.

Source: Rentals.ca

Prior to the pandemic, Canada had an average rental yield of 3.91% on 120-square metre apartments in major city centres. Using this as a baseline, yields appear to have risen slightly in Toronto and Montreal amid the pandemic but fell in Vancouver. Yields outside the city centres also appear to be greater than those inside.

Data on rental yields are generally broken down into two categories: rental properties inside the city centre and outside of the city centre.

| City | Gross Rental Yield (City Centre) | Gross Rental Yield (Outside Centre) |

| Toronto | 3.93% | 4.02% |

| Oakville | 4.07% | 5.10% |

| Mississauga | 5.06% | 5.69% |

| Ottawa | 6.93% | 8.33% |

| Hamilton | 4.86% | 6.15% |

| London | 6.70% | 7.26% |

| Windsor | 5.80% | 6.95% |

| Montreal | 4.63% | 5.12% |

| Winnipeg | 7.94% | 7.26% |

| Calgary | 6.13% | 7.18% |

| Edmonton | 6.89% | 8.52% |

| Vancouver | 3.79% | 3.69% |

| Victoria | 5.14% | 6.64% |

| Canada | 4.69% | 5.60% |

Source: Numbeo

Looking Ahead: What’s Next?

The impact of COVID on the Canadian economy is still unfolding, although there appears to be light at the tunnel with new vaccines set for distribution in the new year. Canada’s deputy chief public officer believes most Canadians could be vaccinated against the virus by late 2021, which bodes well for public health and the economy.

In the meantime, it’s clear that the pandemic has contributed to inequality by widening the chasm between high- and low-income earners. Housing remains a primary vehicle for wealth generation, especially in the highly desirable single-family property market.